Solanum Cheesmaniae, “the” Galapagos Island Tomato.

Like Corn (Maize) and it’s ancestor Teosinte, Tomatoes have wild relatives as well. And what a variety of species they have too! My love and interest in growing, observing, and breeding with these wild tomatoes, like tesosinte, is only continuing to grow.

The wild tomato that I learned about first, and led me down this path, was the almost mythical “Galapagos Island Tomato”. From the same famous islands visited by Charles Darwin in his expedition to catalog biological diversity in all it’s forms. And what better place to start learning about wild tomatoes than from the Galapagos Islands (Ecuador), an enchanting place steeped in biological diversity.

There are actually two main species of native Galapagos Island tomatoes, Solanum cheesmaniae and Solanum galapagense, and they are closely related. Originally, S. galapagense was thought to just be a subspecies of S. cheesmaniae, but was later discovered to be a separate species fairly recently by Sarah Darwin, the great great granddaughter of Charles Darwin. Interesting to see a family legacy of scientific inquiry passed down, but also somehow fitting.

One form of Solanum cheesmaniae leaves and growth pattern.

Both forms are said to be quite salt tolerant (S. galapagense in particular) and may posses some disease resistance. But they also still retain many traits in common with domestic tomatoes and are easily crossbred with them. This salt tolerance is one reason why these tomatoes are so sought after for introgression into modern tomato varieties. Crops that can survive in the harshest of climates and that could be watered with sea water rather than the worlds increasingly limited supply of fresh water is one high area of worldwide interest.

Solanum galapagense, small orange hairy fruits.

Both S. cheesmaniae and S. galapagense are very different in appearance and traits despite both originally thought to be the same species, though similar in many respects. I find the scent of S. cheesmaniae leaves to be of a mild lemony scent but with a strange overtone along with it. The smell of S. galapagense is much stronger with still a sort of lemony smell but a very pugent after odor as well. One person i talked to went to the extreme as saying it smelled like “burning garbage”. Haha, i wouldn’t go that far, but it is an odd smell indeed. Not exactly pleasant.

one example of typical S. galapagense leaf shape and typical sickly yellow appearance.

S. galapagense is of particular interest because not only does it have salt tolerance as well (if not more so that S. cheesmaniae), but it also has unique pest resistance to the common whitefly, a major domestic tomato pest that can spread disease and decimate tomato crops. Solanum cheesmaniae however does not contain this resistance to whitefly, nor do many of the other wild tomato species either. And of those rare few accessions that do, S. galapagense beats them hands down. This is due in part by two factors. One is that it is densely covered in type IV glandular trichomes, or hairs, while simultaneously producing volatile acyl sugars which help repel insects. A sort of bug repellent and/or insecticide. Pretty cool, huh?

Additionally S. galapagense is the more interesting species anyway, by way of genetic diversity and divergence from domestic tomato DNA / genomes. According to one study, that compared to the DNA of S. galapagense, S. cheesmanie, and domestic tomato S. lycopersicum, they found that S. cheesmaniae shares 71.5% of DNA markers with domestic tomatoes, while S. galapagense only shares 57.6% of it’s DNA markers with domestic tomatoes. With only of about 50% DNA markers being shared between S. cheesmaniae and S. galapagense.

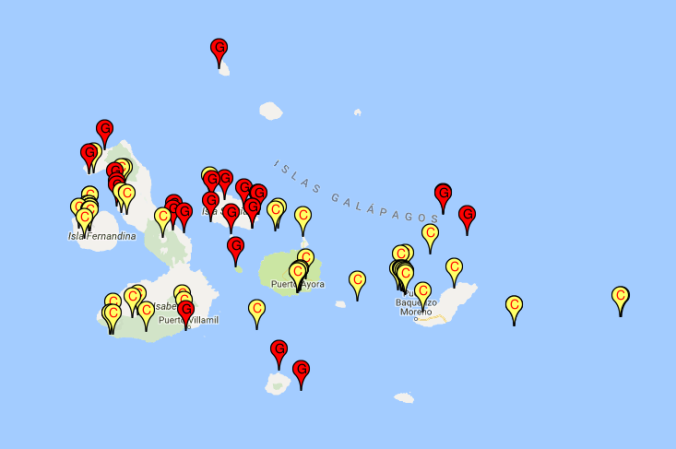

Distribution map for S. cheesmaniae and S. galapagense on the Galapagos Islands.

A map of the distribution of S. cheesmaniae and S. galapagense shows that S. galapagense is not present on the eastern islands. This has led to speculation and conflicting data about the origins of both species and evolutionary distribution on the islands. One study suggests a colonization from east to west , from older to younger islands, supported also by the fact that ocean currents average an east-west direction. If the colonization of Galapagos Islands was east to west, then S. cheesmaniae could be an older species than S. galapagense, and could even be an ancestor to it.

However, high diversity in the S. cheesmaniae group and its correlation with the islands of origin were also suggested. This indicates a possible influence of the movement of the islands, from west to east, on the gene flow, which is the opposite direction. And the lower genetic variation in S. cheesmaniae found in the older islands could possibly be due to a founder effect, and colonization could have happened from west to east. If this was the case, S. cheesmaniae and S. galapagense could have diverged around the same time from the same ancestor. So in short, while that is all fascinating speculation about whether S. cheesmaniae is descended from S. galapagense, or S. galapagense is descended from S. cheesmaniae, or whether they both diverged from a common ancestor we just don’t know. I personally am inclined to believe based on the evidence (until further studies come forth) that both diverged from a common ancestor and moved east to west. Older populations of S. galapagense could possibly have been eradicated on the eastern islands from continual volcanic eruptions and S. cheesmaniae could have been reintroduced onto the eastern islands by traveling animal species. We just don’t know.

One word of caution though if you decide to go looking for seeds for these Galapagos Island tomatoes. You almost certainly wont find pure S. cheesmaniae or pure S. galapagense seeds out there except direct from a seedbank. There are a LOT of snake oil salesmen out there that claim to have them, but while it is possible that they have some wild galapagos tomato heritage, these varieties are almost certainly not pure. Some may very well have S. cheesmaniae ancestry, but are not pure. I have yet to grow out many accessions of S. cheesmaniae and access the genetic diversity in the species, but one that set fruit this last season was about the size of about the nail of my ring finger. Super tiny. One way you can tell if they might be authentic is if the seeds themselves are incredibly small. But if they are the same size as regular tomato seeds they are not pure.

A company that sells one of these hybrid tomatoes, but refuses to post my honest 5 star review is Terrior Seeds / Underwood Gardens. They have a lovely Galapagos Island tomato hybrid that was indeed collected from there , but is actually a hybrid. They refuse to believe me or publish my review despite it being one of my favorite tomatoes to grow and eat. Despite this, i still recommend buying and growing it, but just know that it is a naturally occurring hybrid. https://store.underwoodgardens.com/Wild-Galapagos-Tomato-Solanum-cheesmaniae/productinfo/V1182/

Both S. cheesmaniae and S. galapagense seem to be day length sensitive and only set fruit for (like some of the other wild tomatoes and hybrids) at the very end of the season in August-September. Some did not set fruit at all. A common myth of the Galapagos tomatoes is that they are hard to germinate with the reason being that they evolved to pass through the stomach of a tortoise before germinating. It is true that they are some-what hard to germinate, but they are not impossible to germinate without treatment with bleach or acetic or tartartic acid.

Germination is variable in this regard, and considering that not all islands where S. cheesmaniae and S. galapagense are found, don’t even have tortoises that visit them makes this supposition seem dubious at best. There could be some adaption to the islands in regards to germination, but i am inclined to believe at this point in time that it is an adaption to the soil with high volcanic ash (and thus high pH). After all, many if not most of the accessions of these from the TGRC directly mention that they were growing out of cracks in lava flows. A coincidence? I think not. Recommended seed treatment 50% bleach 50% water does indeed help germination a bit, but it is also recommended to prevent disease and seed borne pathogens. I suspect even soaking the seeds in plain water or soaking in lemon juice may also help germination, but i have yet to do an experiment that tests this idea.

It is obvious that the Galapagos continues to amaze us with it’s fantastic contributions to biological diversity, but what about some of the other wild tomato species? What secrets do they hold for the future of tomato breeding and future tomato varieties? It turns out a lot. Quite a lot actually.

—

LA1777, Solanum habrochaites fruit, photo by Joseph Lofthouse.

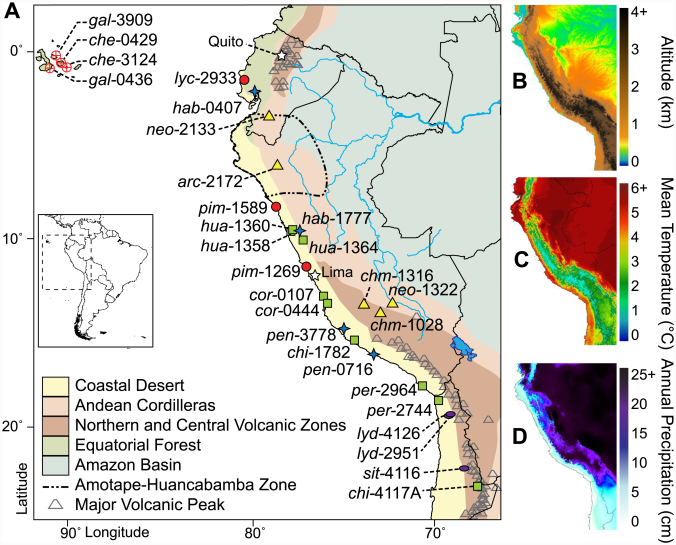

Solanum habrochaites is the next species that researchers are paying attention to. It is from Ecuador and Peru in South America. It is hard to cross with domestic tomato lines, though not impossible, generally through one-way crosses by using the wild parent as the pollen donor and the domestic parent as the pollen recipient. It turns out lots of domesticated plants work this way, having lost the pickiness of their pollen receptors, while wild species are very picky about what pollen they accept.

Solanum habrochaites, bold floral display. Photo by Joseph Lofthouse.

S. habrochaites has lots of genetic diversity within it’s species clade. One, like the most commonly requested accession, LA1777, is a unique off-type. Compared to the rest of the species of S. habrochaites, accession LA1777 has been classified as unique and having genes that may be desirable for introgression into commercial tomatoes.

LA1777 tends to grow small delicate and wispy. The stems on LA1777 are thin and only a couple feet long. The stems on other habrochaites accessions are thick, and grow 4 to 6 feet long. The stem on LA1777 is fibrous. The stems on other accessions snap when bent, like one might snap a young green bean. The leaves on LA1777 are smaller than other accessions.

LA1777 has an unobtrusive floral display that gets lost in the foliage. The floral displays on the other accessions were bold and carried high above the foliage. LA1777 is reported as having better tasting fruits, and not as much brown coloration in the fruits. And though it is reported as being Self incompatible (SI), it somewhat behaves as if it is Self Compatible, at least to some degree. S. habrochaites has both Self-Incompatible and Self-compatible forms.

It is sort of ironic then that LA1777 is the most requested accession of S. habrochaites from the TGRC even though it does not represent the species very well as a whole. However this may be explained by the fact LA1777 has become sort of standard accession in university research and published articles reflect that. But also from the research being done by big seed companies as well. One of the big seed companies tested LA1777 and found one unique gene that nearly doubles production of commercial tomatoes when it is introgressed into breeding lines. Between the university research and the seed companies, LA1777 has become the standard variety for most research on this species of tomato.

But caution should be noted as there may be much more diversity and worthwhile genetics in S. habrochaites than in just accession LA1777. I find it to be poor research that most of these published university studies have ONLY used ONE accession in comparison to domestic tomato varieties, namely accession LA1777. Shame on them.

LA1777 on left, F1 hybrid on right. Solanum habrochaites outlier accession.

Solanum habrochaites, photo by Joseph Lofthouse.

Solanum habrochaites, photo by Joseph Lofthouse.

—

S. peruvianum illustration, year 1828.

Solanum peruvianum is a well known and highly interesting wild tomato species. It’s name obviously hints at it’s origins being from northern Peru and Chile. Solanum peruvianum was originally thought to be a very diverse species of wild tomato, and it still may have much diversity, however it recently has been reclassified into four separate species: Solanum peruvianum, Solanum corneliomuelleri, Solanum huaylasense, and Solanum arcanum.

Solanum peruvianum has purplish fruit when ripe, along with green stripes similar to S. habrochaites. The fruits are said to be fruity and pleasant tasting when fully ripe, but not before. S. peruvianum is said to be harder to cross with commercial tomatoes. However, by using a bridge species that is more readily able to cross with domestic / commercial tomatoes it is said to be possible to move the S. peruvianum genome into the domestic tomato genome.

S. peruvianum flowers, highly attractive to solitary bees in North America. Photo by Joseph Lofthouse.

S. peruvianum might have interesting genetics for it’s fruit characteristics and sugars. It also is said to contain some salt tolerance and ability to grow in harsh areas unhindered. It is also resistant to the tomato leaf curl virus. S. peruvianum is a mostly outcrossing species (Self-incompatible), with some Self-compatible accessions known and collected from isolated specimens. It seems to be fairly drought tolerant in my experience.

One of two species of bumble bees that loved Solanum peruvianum flowers in my garden, Colorado, USA.

—

S. chilense, flowering

Solanum chilense hails from the desert regions of southern Peru and Chile and hasn’t had much research attention paid to it, and thus i don’t have very much information about to share. However it has had some, and it has three main claims to fame. The first is that it is often cited as being a bridge species for S. peruvianum, and other distant species such as S. sitiens and S. lycopersicoides.

The second is that is said to be quite drought tolerant, having a unique root system unlike the other species that allows it to have a very deep root structure. In a desert environment having a deep root structure could be invaluable for surviving rough times.

The third is that this species supposedly has anthocyanin colored fruits and contains the “Aft” gene. The “A” gene being the gene that codes for anthocyanin production, and the “ft” referring to fruit. Haha, simple, but effective terminology.

The Aft gene has been introgressed from S. chilense into domestic tomato breeding lines and is directly responsible (in conjunction with other anthocyanin introgressed genes from S. cheesmaniae) for those new “Blue Tomatoes” you have been seeing on the market now. ‘Indigo Rose’ being the first official tomato variety of this kind. Indigo Rose, was developed from the Oregon State University tomato breeding program. The P20 blue tomato was a leaked breeding line from OSU that eventually became ‘Indigo Rose’. Indigo Rose was released after it was clear that many tomato breeders were already using P20 to breed better tasting blue tomatoes. ‘Indigo Rose’ does not have the best flavor as do most blue tomatoes at this time, but that is steadily being changed as more tomatoes are bred and crossed with each other for better flavor.

The ‘Aft’ tomato (LA1996), growing in N. Colorado in 2017.

This last year, i had the opportunity to grow one of the precursor blue lines to ‘Indigo Rose’, LA1996, which is a determinate tomato, bears fairly large fruit, and has the Aft gene for anthocyanin fruit. LA1996 however does not have blue tomatoes, but rather a dirty blue speckled appearance. I kind of like it though, and i found it to be one of the few tomato varieties to do well in my garden, so i am keeping it. A great tomato variety for me. I have simply just been calling it ‘Aft’. Haha, not very original, but i don’t care.

—

Solanum pennellii, a wild tomato species from Peru, with waxy leaves that help with drought tolerance.

The next species that holds great promise is Solanum pennellii from the dry regions of Peru. This species holds a wealth of potential genetics that domestic tomatoes could benefit from. The first is it’s small unique shaped leaves. These leaves also have a unique thick waxy coating on them that has been shown to help with conserving moisture and providing one form of drought tolerance. This is a completely different desert / drought tolerance adaption than S. chilense’s root structure, how exciting!

Solanum pennellii flower close-up view. Notice how it has loose anthers and a unique curved and exerted stigma.

The excitement for S. pennellii does not end there however. Next notice the flower structure of this species. S. pennelli has both Self-Compatible (SC) and Self-incompatible (SI) forms, though the SI forms are more common. Like, S. habrochaites and many of the other wild species, This self-incompatibility or mandatory-outcrossing nature helps to ensure maximum genetic diversity within the species as possible.

The self-compatible species, including Solanum lycopersicum – the domestic tomato, Solanum pimpinellifolium, S. cheesmaniae, and S. galapagense, all have small uninteresting flowers with tight flower structures, non-exerted stigmas, and closed anther cones which make it hard for pollinating insects to visit them or make it worth their time.

This combination of large open flowers, exerted stigma, and unconnected anthers in S. pennellii make it very attractive to solitary bee species, including small Colletidae bees, Halictidae bees, and of course various species of bumble bees.

Solanum pennellii however has been praised in articles as being the most interesting species of wild tomato to work with because of unique acyl compounds. Basically the compounds that contribute to scent and flavor in fruit. Some Acyl sugars can be astringent and bitter, but some can contribute significantly to pleasant traits as well. Since S. pennellii differs from the common cultivated tomato quite significantly in this regard it is a highly interesting species to work with as it may lead to new tomato flavors and smells. I would regard S. pennellii to be the nicest smelling tomato species i have worked with yet because many of the F1 and F2 hybrids between [S. pennellii x domestic tomato] neither have the standard smell of domestic tomatoes, nor the sometimes stinky smell of some of the other species, instead on average S. pennellii hybrids smell quite like lemon-basil. A very nice smell for a tomato plant.

F1 hybrid [domestic tomato x S. pennellii]. HUGE monster plant with wide branching growth. Highly attractive to native pollinating bees.

—

And finally, the last two wild tomato species i am going to mention are Solanum sitiens and Solanum lycopersicoides, two tomato species unique within the tomato clade. These two species, while probably having other traits in common with other wild tomatoes such as possible drought or salt tolerance, or disease tolerance, or blue fruits (S. lycopersicoides), their real uniqueness lies in the scented flowers they carry.

In all the groups of the domestic and wild tomatoes, none, other than these two species carry scented flowers. Perhaps a trait lost long ago and never really needed. Whatever the case may be, these two distant species carry scented flowers to attract various pollinating insects. S. sitiens flowers are described as stinky and volatile, with a “mothball-like” odor. Presumably this scent works best at attracting flies or beetles which may prefer the stinky smell. S. lycopersicoides on the other hand has flowers which are described as sweet and nectar-like, presumably to attract various bee or moth species that collect nectar. Studies between these two species and the distinct pollinators that visit them would be quite fascinating, especially when put into the subject of adaption, diversification, and evolution.

—

Breeding domestic tomatoes with wild tomatoes is a slow process. But it is interesting and the amount of segregating diversity is endless. Here are some photos of F1 tomato hybrids, F2, and various Back-crosses and segregates.

Oh, and p.s. before i end this post, please note that i have started an experimental plant breeding wiki on my test website. I don’t claim it to be very good, but i am working on posting good pictures of wild tomatoes so that i can have a good reference to look back on to identify specific tomato species and the traits they have. Nobody other than myself will probably find such a wiki useful or interesting, but if for nothing else i want it for myself. There is currently extreme outdated or spotty, or missing info about these tomato species on wikipedia currently and the web is scattered with various information in little nooks and crannies. I wanted a central location that was easy to find. Hence, my tomato wiki.

Feel free to create an account and add your own photos or corrected information or cited sources to the wiki. The more people that help, the better it will be. The more photographs of various diverse species and accessions and angles and growers will also help a tremendous amount as well. Thank you.

https://biolumo.com/index.php?title=Tomato_Breeding_Database